______________________________________________________________________________

June 14, 2003, Associated Press, L.A. Times, Father Divine's Movement Slowly Fades,

Since his death in 1965, the faithful and his landmark real estate holdings have dwindled. But some still believe he is God.

GLADWYNE, Pa. — They keep a place set for Father Divine in the grand dining room at Woodmont, the French Gothic manor where he once greeted thousands of followers who believed he was God.

His office there is just as it was at his death in 1965 -- down to the vintage television across from his desk. When his widow, Mother Divine, used the room for a recent interview, she left his big chair empty and pulled up a seat beside it.

"Father is here with us," she said with a smile, meaning it literally.

Since his death, his widow and other believers have done their best to preserve Father Divine's presence and sustain the religious movement he founded in New York during the first half of the 20th century.

The International Peace Mission still maintains its hilltop estate in Gladwyne, outside Philadelphia; church offices in downtown Philadelphia; and a budget hotel -- the Divine Tracy -- near the University of Pennsylvania campus.

Believers, most of whom are in their 70s and 80s, still gather regularly to sing religious and patriotic songs and listen to recordings of Father Divine's sermons.

But there are signs the movement is in its twilight.

The Peace Mission has spent the last two decades selling many of the landmark properties Father Divine amassed with donations from the faithful in the 1930s, '40s and '50s. Two Philadelphia properties -- the Divine Lorraine Hotel and the Unity Mission Church -- have been sold since 2000.

"Basically we have not changed. We just don't have the people we once had," Mother Divine said.

History hasn't quite decided what to make of Father Divine, a preacher who rose from obscurity by advocating a strict moral code -- and by convincing thousands of people that he was God.

A plaque outside the Divine Lorraine describes Father Divine, who was black, as a civil rights leader. Critics said he was a huckster who talked followers out of their savings.

His early history, and even his real name, are matters of mystery.

Journalists in the movement's heyday said he was probably born George Baker and mowed lawns in Baltimore before he became a preacher and settled in New York.

His congregation experienced its first significant growth after he moved with his disciples to Sayville, on Long Island, in 1919. There, he offered free weekly banquets and help finding jobs to a growing number of mostly black followers attracted by his message of "practical Christianity."

He urged believers not to drink, smoke, swear, gamble or borrow money and to pool their resources and practice communal living.

Followers also eschewed "undue mingling of the sexes." Men and women lived in separate quarters -- a tradition kept alive at the Divine Tracy, where male and female guests stay on separate floors.

Father Divine barred followers from marrying too -- although he had married -- saying that they should give up traditional bonds in favor of membership in a universal family. He also rejected racial identity, urging people to think of themselves simply as Americans.

Those teachings were largely overshadowed by his claim to divinity, which he began to make in his sermons in the 1930s.

According to the movement's beliefs, Christ did not have the power to fully emancipate man so he died and returned as Father Divine. Since his death, believers have said that Father Divine simply "laid down his body," much as Jesus did before him.

The declaration that he was God captivated the New York press, especially after Father Divine was hauled into court on public nuisance charges in 1931.

A judge sentenced him to a year in jail, then, four days later, died unexpectedly. Interviewed in prison, Father Divine reportedly said, "I hated to do it." Weeks later, he was set free.

After that, the sect became a phenomenon. Father Divine moved his base to Harlem, where he acquired hotels and converted them into "Heavens" where followers lived and worked.

Similar Heavens opened in Maryland, New Jersey and Pennsylvania. Through it all, the church's key activity was operating dining halls that provided free food to thousands. Later the mission began charging for the meals, but only a few cents.

Believers said the meals were miracles. Skeptics weren't so sure.

Hundreds of supporters turned over their weekly salaries to the movement, and critics said the cash bought Father Divine luxury cars, fine suits and choice real estate in previously all-white enclaves.

Robert Weisbrot, a Colby College history professor who studied Father Divine, said some of the criticisms are valid.

"Did he get something out of it? Yes, he did," he said. "But it is remarkable how many people over the years counted on him for a cheap meal, cheap lodging, or a cheap Sunday banquet."

The suggestion of impropriety still bothers Mother Divine. She attributes it to prejudice. "He wasn't the established church, and he wasn't the right complexion," she said.

After years of fending off accusations, Father Divine took the movement to Philadelphia in 1942, eventually acquiring the businesses and properties which are now mostly gone.

_______________________________________________________________________________

Jim Hougan: Investigative Notes

["Guyana Operations," After-Action Report, 18-27 November, 1978, prepared by the Special Study Group, Operations Directorate, USMC Directorate, Joint Chiefs of Staff (distributed 31 January, 1979).

At the Temple’s residence in Georgetown – a modest house called “Lamaha Gardens” – a woman named Sharon Amos was told by radio of the ambush at Port Kaituma. She also learned that Jones intended to pull the plug on Jonestown and the more than 900 people who lived there. Taking her children into the bathroom, Mother Amos dutifully slit their throats, then took her own life, as well.

News of the horror quickly got out, but nothing further was heard from Jonestown itself. The “agricultural settlement” was a black hole.

When the Embassy learned of the ambush from one of the returning pilots, Adkins got on the radio – and stayed on the raido for hours – listening hard. For a long while, nothing could be heard. But int he early morning hours of November 19, the voice of Odell Rhodes was suddenly heard, transmitting almost hysterically. After witnessing so many murders and suicides, Rhodes had used a pretext to get past a cordon sanitaire of Temple guards armed with shotguns and crossbows. Reaching the relative safety of the surrounding jungle, he’d made his way to the little police station in nearby Mathews Ridge. It was from there that he broadcast the report that stunned Adkins.

As for Dwyer, he appears to have played a courageous role at the airstrip that night, taking care of the wounded and the dead at considerable risk to himself.

Even so, mysteries remain.

One of them concerns the so-called “Last Tape.” This was a cassette found in a tape-recorder beside Jim Jones’s lifeless body. On the tape, we can hear people wailing and screaming, when Jones suddenly asks, “And what comes, folks, what comes now?”

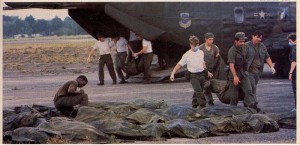

Wikipedia captions this image, "Photograph of military personnel carrying bodies of the victims of the Jonestown massacre out of a helicopter." However, this does, indeed, appear to be a C-141 aircraft. This image is from "the Jonestown Institute" at San Diego State University.

________________________________________________________________________________

July 2nd, 2011, Jim Jones and the Peoples Temple Part 2, by Jim Hougan,

Still, we’re not done with CIA. Its relationship to Jim Jones and the Peoples Temple, and therefore to the Jonestown massacre, is an important issue that will be discussed in subsequent pages.

Here, however, we are concerned with the initial reports of the massacre. And, in particular with those responsible for labeling the disaster a “mass suicide”—contrary to the evidence being gathered by Dr. Mootoo. The person who seems to have been most responsible for spinning the story in that way was Dr. Hardat Sukhdeo, a psychiatrist.

Dr. Sukhdeo is, or perhaps was, “an anti-cult activist” whose professional interests (according to an autobiographical note) were “homicide, suicide, and the behavior of animals in electro-magnetic fields.” His arrival in Georgetown on November 27, 1978 came only three weeks after he had been named as a defendant in a controversial “deprogramming” case. [Sukhdeo was named with "deprogrammer" Galen Kelly in a suit brought by the Circle of Friends on behalf of Joan E. Stedrak. The suit is believed to have been filed on November 6, 1978] It is not entirely surprising, then, that within hours of his arrival in the capital, Dr. Sukhdeo began giving interviews to the press, including the New York Times, “explaining” what had happened.

Jim Jones, he said, “was a genius of mind control, a master. He knew exactly what he was doing. I have never seen anything like this…but the jungle, the isolation, gave him absolute control.” Just what Dr. Sukhdeo had been able to see in his few minutes in Georgetown is unclear. But his importance in shaping the story is undoubted: he was one of the few civilian professionals at the scene, and his task was, quite simply, to help the press make sense of what had happened and to console those who had survived. Accordingly, he was widely quoted, and what he had to say was immediately echoed by colleagues back in the States.

That Sukhdeo’s opinions were preconceived, rather than based upon evidence, however, seems obvious. Even so, it is clear that he was aware of the work that Dr. Mootoo had done—which, as we have seen, contradicted Sukhdeo’s statements about “mass suicides.”

In an interview with Time, Sukhdeo refers to an “autopsy” that had been performed on Jim Jones in Guyana. This can only have been a reference to Dr. Mootoo’s somewhat cursory examination, in which Jones’s body was slit open on the ground. It is difficult to understand how Sukhdeo could have been aware of that procedure without also knowing of Mootoo’s finding that most of the victims had been murdered.

Dr. Sukhdeo was himself a native of Guyana, though a resident of the United States. He claimed at the time that he’d come to Georgetown at his own expense to counsel and study those who had survived. But that is in dispute.

According to his attorney, Robert Bockelman, Dr. Sukhdeo retained him to prevent his having to testify at the Larry Layton trial in San Francisco. (Layton was a member of the Peoples Temple who participated in the events at the Port Kaituma airstrip.) Dr. Sukhdeo’s primary concern, according to Bockelman, was that it should not be revealed that the State Department had paid his way to Guyana. You see the issue: was Doctor Sukhdeo there to help the survivors—or to debrief them on behalf of some other person or agency? [Asked about this in a recent interview, Sukhdeo continued to insist that he paid his own way to Guyana.]

Nor was this all. Prior to retaining counsel in San Francisco, Dr. Sukhdeo had himself been retained by Larry Layton’s defense attorneys and family. (Indeed, he testified in Layton’s trial in Guyana, where “most of his testimony concerned cults in general and observations about conditions at Jonestown.”) [United States v. Layton, Federal Rules (90 F.R.D. 520/1981), pp. 521-22, in re a "Memorandum and Order Denying Plaintiffs Motion to Compel Production of Sukhdeo Tapes." ] During the time that he was helping Layton’s defense, it appears that Dr. Sukhdeo was also meeting —surreptitiously, according to his own lawyer—with FBI agents. Asked about this, Sukhdeo says that at no time during these meetings did he disclose any confidential communicatins between himself and Layton. [Ibid]

The suggestion that Dr. Sukhdeo may have secretly “debriefed” Jonestown’s survivors on behalf of the State Department (or some other government agency) may seem unduly suspicious. On the other hand, a certain amount of suspicion would seem to prudent when discussing the unsolved deaths of more than 900 Americans who, in the weeks before they died, were preparing to defecten masse to the Soviet Union. The government’s interest in this matter would logically have been intense. [The CIA has stated that, in deference to its Charter, which prohibits the Agency from collecting information on Americans, it took no notice of the Temple's approaches to Communist Bloc organizations in Guyana. The disclaimer is widely disbelieved.]

It is true, of course, that not every psychiatrist agreed with Dr. Sukhdeo’s analysis. Dr. Stephen P. Hersh, then assistant director of the National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH), commented that “The charges of brainwashing are clearly exaggerated. The concept of ’thought control’ by cult leaders is elusive, difficult to define and even more difficult to prove. Because cult converts adopt beliefs that seem bizarre to their families and friends, it does not follow that their choices are being dictated by cult leaders.” [Associated Press, story by Chris Connell, November 21, 1978.]

That said, there is more at stake here than public perceptions. Investigators of the Guyana tragedy have a responsibility to both the living and the dead: to find out what actually happened, and to make certain that it cannot happen again.

II.1 THE DOG THAT DIDN’T BARK

To understand the fate of the Peoples Temple, one must first understand why the intelligence community seemed (against all odds) to ignore the organization for so long—appearing to become interested only when Congressman Ryan began his investigation. Consider:

Image from a Peoples Temple brochure, portraying leader Jim Jones as the father of the "Rainbow Family". Image courtesy of The Jonestown Institute, http://jonestown.sdsu.edu.

The Peoples Temple was created in the political deep-freeze of the 1950s. From its inception, it was a leftwing ally of black activist groups that were, in many cases, under FBI surveillance. [For many years, the FBI maintained a "Racial Intelligence" file. A 1968 Airtel sent to that file refers to the Bureau's concerns the possible emergence of an American "Mau Mau," the "rise of a (black) messiah," and "the beginning of a true black revolution."] During the 1960s, when the Bureau and the CIA mounted Operations COINTELPRO and CHAOS to infiltrate and disrupt black militant organizations and the Left, the Temple went out of its way to forge alliances with leaders of those same organizations: e.g., with the Black Panthers’ Huey Newton and with the Communist Party’s Angela Davis. And yet, despite these associations, and its ultra-left orientation, we are told that the Temple was not a target of investigation by either intelligence agency.

In the early 1970s, suspicions began to surface in the press, implicating the Peoples Temple in an array of allegations including gunrunning, drug-smuggling, kidnapping, murder, brainwashing, extortion and torture. Under attack at home, and feeling the pressure abroad, Temple officials undertook secret negotiations with the Soviet Embassy in Georgetown, laying the groundwork for the en masse defection of more than a thousand poor Americans. According to the CIA, it took no interest in these discussions.

Under the circumstances, only the most naive could fail to be skeptical of the disinterested stance that the FBI and the CIA claim to have taken. But what does it mean? Why would the FBI and the CIA give the Peoples Temple a pass?

The answers to those questions are embedded in the contradictions of Jones’s own past and, in particular, in that most mysterious period in the preacher-man’s life: the 1960-64 interregnum that his biographers gloss over. As I intend to show, the enigmas of Jones’s beginnings do much to explain the bloodshed at the end.

II.2 JONES AND MITRIONE IN RICHMOND

Jim Jones was born in Crete, Ind. in 1931. When he was three, he moved with his family to the town of Lynn.

His father was a partially disabled World War I vet. Embittered by the Depression and unable to find work, he is alleged (without much evidence) to have been a member of the Ku Klux Klan. Jones’s mother, on the other hand, was well-liked, a hard-working woman who is universally credited with keeping the family together.

Jones’s religious upbringing took place outside his own family. Myrtle Kennedy, a friend of his mother’s who lived nearby, saw to it that he went to Sunday School, and gave him instruction in theBible. While not yet a teenager, Jones began to experiment, attending the services of several churches. [Raven: the Untold Story of Rev. Jim Jones and His People, by Tim Reiterman with John Jacobs, E.P. Dutton (New York, 1982), pp. 9-21.] Before long, he came under the spell of a “fanatical” woman evangelist, the leader of faith-healing revivals at the Gospel Tabernacle Church on the edge of town. [It is Jones's biographer, Tim Reiterman, who characterizes the unidentified woman evangelist as "fanatical." See Raven, p. 18.] (This was a Pentecostal sect of so-called “Holy Rollers,” a charismatic group then believed in faith-healing and speaking in tongues.) Whether there was more to their relationship than that of a priestess and her protege is unknown, but it is a fact that Jones’s association with the woman coincided with the onset of nightmares. According to Jones’s mother, he was terrorized by dreams in which a snake figured prominently.[The possibility that Jones was sexually abused as a child should not be ruled out---particularly in light of his own abusive sexual behavior as an adult. Even those who remain loyal to Jones, insisting that he was somehow "misunderstood," lament his enthusiasm for sexually humiliating those who had displeased him---not occasionally by resorting to homosexual rape.]

Whatever the nature of his relationship to the lady evangelist, Jones soon found himself in the pulpit, dressed in a white sheet, thumping the Bible. The protege was a prodigy and, by all accounts, he loved the attention.

In 1947, 15-years-old and still a resident of Lynn, Jones began preaching in a “sidewalk ministry” on the wrong side of the tracks in Richmond, Ind.—sixteen miles from his home. Why he traveled to Richmond to deliver his message, and why he picked a working-class black neighborhood in which to do it, is uncertain.

What is certain, however, is that, while in Richmond, Jones established a relationship with a man named Dan Mitrione. Like the child evangelist, Mitrione would one day become internationally notorious and, like Jones, his violent death in South America would generate headlines around the world. As Jones told his followers in Guyana,

Myrtle Kennedy has confirmed that the two men knew one another, saying that they were friends. [ It was independent researcher John Judge who asked Kennedy about Jones's relationship to Mitrione.]

That Jones knew Mitrione is strange coincidence, but not entirely surprising. A Navy veteran who’d joined the Richmond Police Department in 1945, Mitrione worked his way up through the ranks as a patrolman, a juvenile officer and, finally, chief of police. It is unlikely that he would have overlooked the strange white-boy from Lynn preaching on the sidewalk to blacks in front of a working-class bar on the industrial side of town.

What is surprising about Jones’s statement, however, is his description of Mitrione as a “vicious racist.” There is nothing anywhere else to suggest that Mitrione held any particular views on the subject of race. Communism, certainly—but race, no. [A book about Mitrione, and his 1970 assassination in Uruguay, is Hidden Terrors, by A.J. Langguth, Pantheon Books (New York, 1978).]

What is surprising about Jones’s statement, however, is his description of Mitrione as a “vicious racist.” There is nothing anywhere else to suggest that Mitrione held any particular views on the subject of race. Communism, certainly—but race, no. [A book about Mitrione, and his 1970 assassination in Uruguay, is Hidden Terrors, by A.J. Langguth, Pantheon Books (New York, 1978).]

Which is to say that either Jones was wrong about the Richmond cop, or else he knew something about Dan Mitrione that other people did not.

If Mitrione were to play no further part in Jones’s story, there would be little reason to speculate any further about their relationship. But, as we’ll see, Jones and Mitrione cross each other’s paths repeatedly, and in the most unlikely places. Neither family friends nor playmates (Mitrione was eleven years older than Jones), their relationship must have been based upon something. But what?

If Mitrione were to play no further part in Jones’s story, there would be little reason to speculate any further about their relationship. But, as we’ll see, Jones and Mitrione cross each other’s paths repeatedly, and in the most unlikely places. Neither family friends nor playmates (Mitrione was eleven years older than Jones), their relationship must have been based upon something. But what?

Two possibilities suggest themselves: either Mitrione was counseling in Jones in the way policemen sometimes counsel children, or their relationship may have been professional. That is to say, Mitrione may have recruited Jones as an informant within the black community. This second possibility is one to which we’ll have reason to return.

II.3 JONES IN THE FIFTIES

Very little research seems to have been carried out by anyone with respect to Jones’s early career. It is almost as if his biographers are uninterested in him until he begins to go off the deep end. This is unfortunate—particularly in light of the possibility that Jones may have been a police or FBI informant, gathering “racial intelligence” for the Bureau’s files.

What is known about his early career is, therefore, known only in outline.

He graduated from Richmond High School in about January, 1949, and began attending the University of Indiana at Bloomington. [Jones moved from Lynn to Richmond in the Fall of 1948.]He was married to his high school sweetheart, Marceline Baldwin, in June of the same year.

In the Summer of 1951, Jones moved to Indianapolis to study law as an undergraduate. While there, he began to attend political meetings of an uncertain kind. Ronnie Baldwin, Marceline’s younger cousin, was living with the Joneses at the time. And though he was only eleven years old, Baldwin recalls that Jones sometimes took him to political lectures. On one such outing, Baldwin remembers, he and Jones went to a “churchlike” auditorium where “communism” was under discussion. They didn’t stay long, however. Soon after they’d arrived, someone came up to Jones and whispered in his ear—whereupon Jones took his ward by the arm and exited hurriedly. Outside, Jones said “Good evening” to a man whom Baldwin believes was an FBI agent. [Op cit.,Raven, p. 40]

It’s a peculiar story, and Jones’s biographers don’t seem to know what to make of it. What sort of meeting could it have been? The assumption is made, in light of Jones’s later politics, that it was a leftist soiree of some kind. After all, they were talking about communism. But that makes very little sense. Indianapolis was a very conservative city in 1951. (It still is.) Joe McCarthy was on the horizon, and the Korean War was beginning to take its toll. If “communism” was being discussed in anything other than whispers, or anywhere else than a back-room, the debate was almost certainly one-sided and thumbs-down.

It was at about this same time that Jones gave up the study of law and, to everyone’s surprise, decided to become a minister. By 1952, he was a student pastor at the Somerset Methodist Church in Indianapolis and, in 1953, made his “evangelical debut” at a ministerial seminar in Detroit, Michigan.

By 1954, Jones had established the “Community Unity” Church in Indianapolis, while preaching also at the Laurel Tabernacle. To raise money, he began selling monkeys door-to-door. [One hardly knows what to make of this bizarre fund-raising method. There can't have been that much demand for the beasts. Nevertheless, the practice is worth noting, if only because it constitutes, however tenuously, Jones's first known link to South America. Contrary to some reports, the monkeys were not obtained from university research laboratories in Indiana, but from suppliers below the Equator.]

By 1956, Jones had established the “Wings of Deliverance” Church as a successor to Community Unity. Almost immediately, the Church was christened the Peoples Temple. The inspiration for its new name stemmed from the fact that the church was housed in what was formerly a Jewish synagogue—a “temple” that Jones had purchased, with little or no money down, for $50,000.

Ironically, the man who gave the Peoples Temple its start was the Rabbi Maurice Davis. It was he who sold the synagogue to Jones on such remarkably generous terms. A prominent anti-cult activist and sometime “deprogrammer,” Rabbi Davis is an associate of Dr. Sukhdeo’s.

II.4 JONES AND FATHER DIVINE

By the late 1950s, the Peoples Temple was a success, with a congregation of more than 2000 people. Still, Jones had even larger ambitions and, to accommodate them, became the improbable protege of an extremely improbable man. This was Father Divine, the Philadelphia-based “black messiah” whose Peace Mission movement attracted tens of thousands of black adherents and the close attention of the FBI, while earning its founder an annual income in seven figures.

For whatever reasons, beginning in about 1956, Jones made repeated pilgrimages to the black evangelist’s headquarters, where he literally “sat at the feet” (and at the table) of the great man, professing his devotion. With the exception of Father Divine’s wife, Jones may well have been the man’s only white adherent.

It was not entirely inconvenient. Living in Indianapolis, Jones could easily arrange to transport members of the Peoples Temple by bus to Philadelphia—where they were housed without charge in Father Divine’s hotels, feasted at banquets called “Holy Communions,” and treated to endless sermons. [When Father Divine died in the summer of 1972, years after Jones had moved his own congregation to California, Jones nevertheless arranged for a caravan of buses to cross the country to Philadelphia---where Jones announced that he was Father Divine's white reincarnation. In that capacity, he said, he was quite prepared to take control of the Peace Mission movement (and its considerable assets). Mrs. Divine said no.]

That Jones made a study of Father Divine, emulated him and hoped to succeed him, is clear. The possibility should not be ruled out, however, that Jones was also engaged in collecting “racial intelligence” for a third party.

Whatever else Jones may have picked up from his study of Father Divine, there is reason to believe that it was in the context of his visits to Philadelphia that he was introduced to the subject of mass suicide. Among Jones’s personal effects in Guyana was a book that had been checked out of the Indianapolis Public Library in the 1950s, and never returned. In the pages of Father Divine: Holy Husband, the author quotes one of the black evangelist’s followers:

“‘If Father dies,’ she tells you in the calmest kind of a voice, ‘I sure ’nuff would never be callin’ in myself to be goin’ on livin’ in this empty ol’ world. I’d be findin’ some way of gettin’ rid of the life I never been wantin’ before I found him.’ “If Father Divine were to die, mass suicides among Negroes in his movement could certainly result. They would be rooted deep, not alone in Father’s relationship with his followers, but also in America’s relationship with its Negroe citizens. This would be the shame of America.” (Emphasis added.) [Father Divine: Holy Husband, by Sara Harris, pp. 319-20.]

II.5 JONES GOES TO CUBA

In January, 1959, Fidel Castro overthrew the Batista dictatorship, and seized power in Cuba. Land reforms followed within a few months of the coup, alienating foreign investors and the rich. By Summer, therefore, Cuba was in the midst of a low-intensity counter-revolution, with sabotage operations mounted from within and outside the country.

Within a year of Castro’s ascension, by January of 1960, mercenary pilots and anti-Castroites were flying bombing missions against the regime. Meanwhile, in Washington, Vice-President Richard Nixon was lobbying on behalf of the military invasion that the CIA was plotting.

It was against this background, in February of 1960, that Jim Jones suddenly decided to visit Havana.

The news of Jones’s visit to Cuba—one is tempted to write “the cover-story for Jones’s trip to Cuba”—was first published in the New York Times in March, 1979 (four months after the massacre in Guyana). The story was based upon an interview with a naturalized American named Carlos Foster. A former Cuban cowboy, Baptist Pentecostal minister and sometime night-club singer, Foster showed up at the New York Times four months after the massacre. Without being asked, he volunteered a strange story about meeting Jim Jones in Cuba during the Winter of 1960. (Why Foster went to the newspaper with his story is uncertain: news of his friendship with Jones could hardly have helped his career as a childrens’ counselor). [New York Times, "Jim Jones 1960 Visit to Cuba Recounted," by Joseph B. Treaster. As evidence of his veracity, Foster provided theTimes with letters and an affidavit that Jones had signed, promising to support Foster if he should emigrate to the United States.]

Nevertheless, according to the Times story, the 29-year-old Jones traveled to Cuba to expedite plans to establish a communal organization with settlements in the U.S. and abroad. The immediate goal, Foster said, was to recruit Cuban blacks to live in Indiana.

Foster told the Times that he and Jones met by chance at the Havana Hilton. That is to say, Jones gave the Cuban a big hello, and took him by the arm. He then solicited Foster’s help in locating forty families that would be willing to move to the Indianapolis area (at Jones’s expense). Tim Reiterman, who repeats the Times‘ story, adds that the two men discussed the plan in Jones’s hotel-room, from 7 in the morning until 8 o’clock at night, for a week. More recently, Foster has elaborated by saying that Jones offered to pay him $50,000 per year to help him establish an archipelago of offshore agricultural communes in Central and South America. Foster said that Jones was an extremely well-traveled man, who knew Latin America well. He had already been to Guyana, and wanted to start a collective there.

After a month in Cuba, Jones returned to the United States (alone). Six months later, Foster followed, on his own initiative, but the immigration scheme went nowhere. [Foster came to Indianapolis in August, 1960. He accepted the hospitality of the Peoples Temple for the remainder of that Summer, and then decamped for New York (where his fiance was living).]

The anomalies in this story are many, and one hardly knows what to make of them. Foster’s information that Jones was well-traveled in Latin America, and had already been to Guyana, comes as a shock. None of his biographers mentions Jones having taken trips out of the United States prior to this time. Could Foster be mistaken? Or have Jones’s biographers overlooked an important part of his life?

An even greater anomaly, however, concerns language. While Reiterman reports that Foster was bilingual, and that he and Jones spoke English together, this isn’t true. Foster learned English at Theodore Roosevelt High School in the Bronx—after he’d emigrated to the United States. [Ascent, "Lure of the Cowboy Mystique," by Aubrey E. Zephyr, October, 1983. This is an article about Foster's Urban Western Riding Program (for inner-city youngsters).] (Reiterman seems to have made an otherwise reasonable, but incorrect, assumption: knowing that Jones did not speak Spanish, he assumed that Foster must have been able to speak English.)

Today, when Foster is asked which language was spoken, he says that he and Jones made do with the latter’s broken Spanish.

The issue is an important one because Foster is, in effect, Jones’s alibi for whatever it was that Jones was actually doing in Cuba. That the two men did not have a language in common makes the alibi suspect: how could they converse for 13 hours at a time, day in and day out, for a week—if neither man understood what the other was saying?

The issue is an important one because Foster is, in effect, Jones’s alibi for whatever it was that Jones was actually doing in Cuba. That the two men did not have a language in common makes the alibi suspect: how could they converse for 13 hours at a time, day in and day out, for a week—if neither man understood what the other was saying?

As for Jones’s own parishioners, those who’ve survived have only a dim recollection of the trip. According to Reiterman, “Back in the States, Jones revealed little of his plan, depicting his stay more as tourism than church business.” This sounds like a polite way of saying that the trip served no obvious purpose. Nevertheless, he did bring back some strange souvenirs. “He showed off photos of Cuba… One picture—a gruesome shot of the mangled body of a pilot in some plane wreckage—indicated that Jones witnessed the pirate bombings of the cane fields. Jones told his friends that he had met with some Cuban leaders, though the bearded man in fatigues standing beside Jones in a snapshot was too short to be Castro.” [Op cit., Raven, p. 62.]

It would be interesting to know just what Reiterman is talking about here. The presumption must be that there is a photograph in which Jones is seen with a man who might easily be confused with Castro—if it weren’t for the latter’s diminutive size. In fact, however, it probably was Castro. When Jones arrived in Brazil in 1962, he carried a photograph of himself and his wife Marceline, posing with the Cuban premier. Jones said that the picture was taken on a stopover in Cuba on the way to Sao Paulo. [The reference to a Cuban stopover on the way to Brazil, and to a photo of Jones, Marceline and Castro, is told in The Broken God, by Bonnie Thielmann with Dean Merill, David C. Cook Publishing Co. (Elgin, Ill.), 1979, p. 27.] That is to say, in late 1961 or early 1962.

How Jones met Fidel Castro—and why—is an interesting question. So, too, we can only wonder at his proclivity for taking photographs of mercenary pilots in their crashed planes. Pictures of that sort could only have been of interest to Castro’s enemies and the CIA.

Returning to Carlos Foster, if the tale that he told to the Times was a pre-emptive cover-story, a “limited hang-out” of some sort, what was Jones actually doing? Why had he gone to Havana? At this late date, and in the absence of interviews with officials of the Cuban government, there is probably no way to know. What may be said, however, is this:

Returning to Carlos Foster, if the tale that he told to the Times was a pre-emptive cover-story, a “limited hang-out” of some sort, what was Jones actually doing? Why had he gone to Havana? At this late date, and in the absence of interviews with officials of the Cuban government, there is probably no way to know. What may be said, however, is this:

Emigration was an extremely sensitive issue in the first years of the Castro regime. The CIA and the State Department, in their determination to embarrass Castro, did everything possible to encourage would-be immigrants to leave the island. As a part of this policy, U.S. Government agencies and conservative Christian religious organizations collaborated to facilitate departures. [Religion In Cuba Today, edited by Alice L. Hageman and Philip E. Wheaton, Association Press, New York, p. 32.] Jones’s visit may well have been a part of this program.

But there is no way to be certain of that. Cuba was in the midst of a parapolitical melt-down. While the CIA was conspiring to launch an invasion, irate Mafiosans and American businessmen had joined together to finance the bombing-runs of mercenary pilots. Meanwhile, the Soviets had sent their Deputy Premier, Anastas I. Mikoyan, to Havana for the opening of the Soviet Exhibition of Science, Technology and Culture. [Mikoyan was in Havana from February 4-13.] The visit coincided with the Soviets’ decision to give Cuba a long-term low-interest loan, while promising to buy a million tons of Cuban sugar per annum. The “Hilton Hotel” at which Jones was staying was the temporary home of a Sputnik satellite that the Soviets had put on display. According to former CIA officer Melvin Beck, the CIA was trying to photograph it, and the lobby was crawling with spies from as many five different services (FBI, CIA, KGB, GRU and DGI).

[In this connection, an interesting coincidence concerns the presence of New York Times reporter James Reston at the Hilton. He was there to cover the Mikoyan visit, as well as the Soviet exhibition, and it seems fair to say that, in a literal sense, at least, he must have crossed paths with Jim Jones.

It is ironic, then, that nearly twenty years later, his son should one day write a book (Our Father Who Art In Hell) about the decline and fall of the Peoples Temple. And in that book, a peculiar story is told:

"In December, 1978, James Reston, Jr. (met) a journalist friend at the Park Hotel in Georgetown. The journalist announced ominously that he now knew the full story behind Jonestown. But he would not write it. He would not tell his editors he knew it. He would forget it and flee Guyana as soon as possible. He told Reston the name of his informant. "'He will contact you at your hotel. If you want it, you will get the full story. I have just heard it, and I've sent the man away. If I were you, I wouldn't take it either. It will make you the most celebrated writer in America, and you will die for it.'

"Reston felt a nervous laugh rising from his belly and controlled it."

Reston seems not to have pursued the matter.]

It is ironic, then, that nearly twenty years later, his son should one day write a book (Our Father Who Art In Hell) about the decline and fall of the Peoples Temple. And in that book, a peculiar story is told:

"In December, 1978, James Reston, Jr. (met) a journalist friend at the Park Hotel in Georgetown. The journalist announced ominously that he now knew the full story behind Jonestown. But he would not write it. He would not tell his editors he knew it. He would forget it and flee Guyana as soon as possible. He told Reston the name of his informant. "'He will contact you at your hotel. If you want it, you will get the full story. I have just heard it, and I've sent the man away. If I were you, I wouldn't take it either. It will make you the most celebrated writer in America, and you will die for it.'

"Reston felt a nervous laugh rising from his belly and controlled it."

Reston seems not to have pursued the matter.]

While one cannot say that Jones’s 1960 visit to Cuba was necessarily a spying mission, the circumstantial evidence suggests that it was. That is to say, virtually every element of the trip can be shown to have been of particular interest to the CIA: encouraging Cuban emigration; documenting the destruction of aircraft piloted by mercenaries; the Sputnik at the Hilton; and, it would seem, Castro himself.

II.6 JIM JONES, HIS PASSPORT AND THE CIA

Cuba wasn’t the only country to which Jones intended to travel in 1960. On June 28 of that year, at about the same time that Foster arrived in Indianapolis from Cuba, the State Department issued a passport (#2288751) to Jones for a seventeen-day visit to Poland, Finland, the U.S.S.R., and England. The purpose of the trip, according to Jones’s visa application, was “sightseeing – culture.”

Which presents us with an enigma. According to State Department records, this was Jones’s first passport. How, then, did he travel to Cuba in February if he did not receive a passport until the end of June? Did he enter the country “black”? Was he using someone else’s documents? And what about Carlos Foster’s certainty that Jones had previously traveled throughout Latin America? Was Foster mistaken, or had Jones in fact visited Guyana?

It is almost as if we are dealing with two Jim Joneses. And perhaps we are. It’s a subject to which we will need to return.

Here, however, I want to point out certain coincidences of timing in the lives of Jim Jones and Dan Mitrione, and to discuss Jones’s own file at the CIA.

Passports typically require about 4-6 weeks to be mailed out. Since Jones’s passport was issued on June 28, 1960 his application would have been filed in early May. As it happens, it was during that same month that Dan Mitrione was in Washington D.C., being interviewed for a new job with a component of the State Department’s Agency for International Development (AID), the International Cooperation Administration (ICA). An acknowledged cover for CIA officers and contract-spooks such as Watergate’s E. Howard Hunt and the JFK assassination’s George de Mohrenschildt, the ICA would become infamous during the 1960s, funding the construction of tiger-cages in Vietnam, and training foreign police forces in the theory and practice of torture.

A few years earlier, in 1957, Mitrione had spent three months at the FBI’s National Academy.[Mitrione was then Chief of Police in Richmond. ] The connections he’d made stood him in good stead. Immediately after his interview with the ICA, he was hired by the State Department as a “public safety adviser.” Three months later, in September, 1960 he was in Rio de Janeiro, studying Portuguese; by December, he was living with his family in Belo Horizonte, Brazil.

Whether Mitrione was an undercover CIA officer in South America is disputed. The Soviets say he was. [Who's Who in the CIA, by Dr. Julius Mader, Berlin (1968).] Officially, however, Mitrione was an AID officer attached to the Office of Public Safety (OPS). But OPS was very much a nest of spies: in the Dominican Republic during the mid-1960s, for example, six out of twenty positions were CIA covers. ["U.S. A.I.D. In the Dominican Republic - An Inside View," NACLA Newsletter, November, 1970. This was according to David Fairchild, the Assistant Program Officer for USAID in Santo Domingo. (NACLA is the North American Conference on Latin America.) ] Moreover, Mitrione’s partner at the time of his 1970 kidnapping in Uruguay was a public safety officer named Lee Echols—whose previous assignment had been as a CIA officer in the Dominican Republic. ["Echols takes dead aim on laugh," San Diego Union, June 12, 1986, p. 11.]

Whether or not Mitrione was an undercover CIA officer, it is a fact that the CIA’s Office of Security opened a file on Jones, and conducted a name-check on him, coincident with Mitrione’s departure for Rio. Why it did so is a mystery: the Agency won’t say.

It is speculated, of course, that the file and name-check were sparked by the Soviet Bloc destinations for which Jones had applied for a visa. But that could hardly have been the case. The visa requests had been made in May, and the passport issued in June. It was not until November, some five months later, that the Office of Security sent agents to the State Department’s Passport Office, there to examine Jones’s records—an activity that would hardly have been necessary if the passport application had stimulated the name-check in the first place.

Given the CIA’s reluctance to clear up the matter, one can only speculate that the Agency may have been “vetting” Jones for employment as an agent.

Two points should be made here. The first is that the CIA claimed, in the aftermath of the Jonestown massacre, that its file on “the Rev. Jimmie Jones” was virtually empty. According to the Agency, it had never collected data—not a single piece of paper—on Jones or the Peoples Temple. It simply had a file on him.

Which remained open for 10 years. According to CIA record, the file was only closed—and closed without explanation—in the wake of Dan Mitrione’s assassination by Tupamaro guerrillas in Uruguay.

Which is to say that the lifespan of Jones’s file at the CIA coincided precisely with the dates of Dan Mitrione’s tenure at the State Department. What I am suggesting, then, is that Richmond Police Chief Dan Mitrione was recruited into the CIA, under State Department cover, in May, 1960; that a CIA file was opened on Jones because Mitrione intended to use him as an agent; and that Jones’s file was closed and purged, ten years later, as a direct and logical result of Mitrione’s assassination in 1970.

II. 7 JONES IN SOUTH AMERICA

To understand the significance of next occurred, one has to go back more than one hundred years. It was then, in the Northwest District of Guyana, that a prophet named Smith issued a call to the country’s disenfranchised Amerindians, summoning them to a redoubt in the Pakaraima Mountains—the land of El Dorado.

Akawaios, Caribs and Arawaks came from all around to witness what they were told would be the Millennium. “They would see God,” Smith promised, “be free from all calamities of life, and possess lands of such boundless fertility, that a…(large) crop of cassava would grow from a single stick.”

But Smith had lied. And “when the Millennium failed to materialize, the followers were told they had to die in order to be resurrected as white people…

“At a great camp meeting in 1845, some 400 people killed themselves.” [Guyana Gold, by Wellesley A. Baird, Three Continents Press (Washington, 1982), pp. 164-181. The quotation is from an Afterword by Kathleen A. Adams. Ms. Adams wrote her doctoral thesis (for Case Western Reserve University) on the impact of the gold-mining industry on Amerindian tribes in the North West District of Guyana.]

One-hundred-and-thirty-three years later, in the Fall of 1978, at a great camp meeting in the same Northwest District of Guyana, upwards of a thousand expatriate Americans, most of them black, and about as poor and disenfranchised as the Amerindians who’d preceded them, died under circumstances so similar as to be eerie. They, too, had been promised that they would be freed from the calamities of life, and that they would possess lands of boundless fertility. Like Smith, their charismatic leader had a generic sort of name and he, too, had lied.

This time, 913 people died in front of a large, hand-lettered sign that read: “Those who fail to learn from history are condemned to repeat it.”

The coincidence here is so dramatic that is impossible not to wonder if Jim Jones knew of Smith’s precedent. Because, if he did know, and if his politics were, as seems very likely, a fraud, then the Jonestown massacre is revealed to have been a ghastly practical joke—the ultimate psychopathic prank.

According to Kathleen Adams, the anthropologist who first related the story about Smith and the Amerindians, Jim Jones was in fact familiar with the suicides of 1845. He had learned of them, she said, while working as a missionary in the Northwest District.

Adams does not tell us when this was, but the implication is that it was long before the establishment of Jonestown. The possibilities here are two:

The first is that Jones’s Cuban friend, Carlos Foster, is correct when he says that Jones was well-traveled and had been to Guyana prior to 1960. The difficulty with this, of course, is that Jones’s biographers are ignorant of any such travels. But if Jones did not go to Guyaya prior to 1960, he must have learned about Smith’s precedent while doing missionary work in Guyana—after his 1960 visit to Cuba. But when could that have been?

The answer would appear to be at about the end of October, 1961. Arriving at that conclusion is by no means an easy matter, however, given the chronological confusion that his most responsible biographer, Tim Reiterman, relates. [Op cit., Raven, pp. 75-78.] Because this confusion raises a number of interesting questions about Jones’s activities, whereabouts and true loyalties, the matter is worth straightening out.

In the Fall of 1961, Jim Jones was becoming paranoid. Under treatment for stress, he was hearing “extraterrestrial voices,” and suffering seizures. [Dr. E. Paul Thomas was Jones's physician.] Hospitalized during most of the first week in October, he resigned his position as Director of the Indianapolis Human Rights Commission. [Jones's hospital stay is related in the Indianapolis Recorder, October 7, 1961.]

It was then, according to Reiterman, that Jones confided in his ministerial assistant, Ross Case, that he’d had a vision of nuclear holocaust.

“A few weeks later, Jones took off alone in a plane for Hawaii, ostensibly to scout for a new site for Peoples Temple….” (At a loss to explain why Jones should have gone to Hawaii, Reiterman implies that Jones viewed the islands as a potential nuclear refuge—a ludicrous notion in light of their role as stationary aircraft carriers.)

“On what would become a two-year sojourn, Jones made his first stop in Honolulu, where he explored a job as a university chaplain. Though he did not like the job requirements, he decided to stay on the island for a while anyway, and sent for his family. First, his wife, his mother and the children, except for Jimmy, joined him. Then the Baldwins followed with the adopted black child…. During the couple of months in the islands, Jones seemed to decide that his sabbatical would be a long one.” [Ibid., p. 77.]

According to Reiterman’s chronology, therefore, Jones left Indianapolis for Hawaii near the end of October, 1961. He then sent for his family, which joined him in what we may suppose was November. The family remained in Hawaii for a “couple of months”: i.e., until January or February.

“In January, 1962, Esquire magazine published an article listing the nine safest places in the world to escape thermonuclear blasts and fallout….

The article’s advice was not lost on Jones. Soon he was heading for the southern hemisphere, which was less vulnerable to fallout because of atmospheric and political factors. The family planned to go eventually to Belo Horizonte, an inland Brazilian city of 600,000.”

Jones’s biographer goes on to say that, after leaving Hawaii, he subject traveled to California, and then to Mexico City, before continuing on to Guyana. There, Jones’s visit “made page seven of theGuiana Graphic.” [Ibid., p. 78.]

That Jones made page 7 of the local newspaper is a matter of fact. Unfortunately for Reiterman’s chronology, however, he did so on October 25 (1961). Which is to say that the head of the Peoples Temple is alleged to have been in two places at that same time: in Hawaii and Guyana during the last week in October—with intervening stops in California and Mexico City.

Obviously, Reiterman is mistaken, but the issue is not merely one of a confused chronology. There is evidence (including, as we’ll see, a photograph) which strongly suggests that two people may have been using Jones’s identity during the 1961-63 period. Because of this, rumors that Jones was hospitalized in a “lunatic asylum” during that time should not be dismissed out of hand. The rumors were started by a black minister in Indiana who is said to have been jealous of Jones’s success among blacks at the Peoples Temple. While the allegation has yet to be documented, there are many other references to Jones’s having been under psychiatric care at one time or another.

Ross Case says that Jones sometimes referred to “my psychiatrist.” Others have suggested that the real reason Jones went to Hawaii was to receive psychiatric care without publicity.

In later years, Temple member Loretta Cordell reported shock at seeing Jones described as “a sociopath.” The description was contained in a psychiatrist’s report that Cordell said was in the files of Jones’s San Francisco physician (probably Dr. Carleton Goodlett).

In a recent interview with this author, Dr. Sukhdeo confirmed that Jones had been treated at the Langley-Porter Neuropsychiatric Institute in San Francisco during the 1960s and 70s. According to Sukhdeo, he has repeatedly asked to see Jones’s medical file from the Institute, but to no avail.

“I have asked (Langley-Porter’s Dr.) Chris Hatcher to see the file several times,” Sukhdeo told this writer. “But, each time, he has refused. I don’t know why. He won’t say. It’s very peculiar. Jones has been dead for more than 20 years.”

“The nation’s leading center for brain research,” Langley-Porter is noted for its hospitality to anti-cult activists such as Dr. Margaret Singer and, also, for experiments that it conducts on behalf of the Defense Department’s Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA). While much of that research is classified, the Institute has experimented with electromagnetic effects and behavioral modification techniques involving a wide variety of stimuli—including hypnosis-from-a-distance.

Some of the Institute’s classified research may be inferred from quotations attributed to its director, Dr. Alan Gevins (see Mind Wars, by Ron McRae, St. Martin’s Press, 1984, p. 136). According to Dr. Gevins, the military potential of Extremely Low Frequency radiation (ELF) is enormous. Used as a medium for secret communications between submarines, ELF waves are a thousand miles long, unobstructed by water, and theoretically “capable of shutting off the brain (and) killing everyone in l0 thousand square miles or larger target area.”

“‘No one paid any attention to the biological affects of ELF for years,’ says Dr. Gevins, ‘because the power levels are so low. Then we realized that because the power levels are so low, the brain could mistake the outside signal for its own, mimic it (a process known as bioelectric entrainment), and respond when it changes.’”

The process is one that would no doubt fascinate Dr. Sukhdeo. (As an aside, it’s worth noting that virtually every survivor of the Jonestown massacre was treated at Langley-Porter. This occurred as a consequence of San Francisco Mayor George Moscone’s request that Dr. Hatcher undertake a study of the Peoples Temple while counseling its survivors. (Hatcher’s appointment was made with surprising alacrity since Moscone himself was assassinated only nine days after the killings at Jonestown.)

Returning to the Guiana Graphic article about Jones’s visit to Guyana, it is worth pointing out that the story throws a crimp in much more than Reiterman’s chronology. It makes a hash as well of Jones’s motive for going to South America. The Esquire article, published in January, 1962 could hardly have prompted Jones to go anywhere in October, 1961.

So, too, the story in the Graphic provides clear evidence of Jones’s immersion in political intrigue.

At the time of his visit, the former British colony was wracked by covert operations being mounted by the CIA and MI-6.

By way of background, the most important political group in the country was the People’s Progressive Party (PPP), established by Dr. Cheddi Jagan during the 1940s. A Marxist organization, the PPP’s activities had caused the British to declare “a crisis situation” in 1953. Troops were sent, the Constitution was suspended, and recent elections were nullified in order to “prevent communist subversion.”

Over the next four years, MI-6 and the CIA established a de facto police state in Guyana. Racial tensions were exacerbated between the East Indian and black populations—with the result that the PPP was soon split. While Jagan, himself an East Indian, remained in charge of the party, another of its members—a black named Forbes Burnham—began (with the help of Western intelligence services) to challenge his leadership.

Despite the schism, the PPP was victorious in 1957 and, again, in 1961—just prior to Jones’s visit. Coming on the heels of Castro’s embrace of the Soviets, Jagan’s re-election chilled the Kennedy Administration. Accordingly, the CIA intensified its operations against Jagan and the PPP, doing everything in its power to increase its support for Burnham, provoke strikes and exacerbate racial and economic tensions. It accomplished all these goals, secretly underwriting Burnham’s political campaigns, while using the American Institute for Free Labor Development (AIFLD) as a cover for operations against local trade unions.

Eventually, these operations would succeed: Jagan would be ousted, and Burnham brought to power. A decade later, that same Burnham regime would facilitate the creation of Jonestown, leasing the land to the Peoples Temple and approving its members’ immigration.

It was in this somewhat dangerous context that Jim Jones arrived in the Guyanese capital. Putting on a series of tent-shows, replete with faith-healings and talking in tongues, he warned the local populace against thieving American missionaries and evangelists—who, he said, were largely responsible for the spread of Communism.

Even Reiterman, who accepts almost everything at face-value, is puzzled by this: “Entering politically volatile South America,” he writes, Jones “seemed to want to put himself on the record as an anticommunist.” [Op cit., Raven, p. 78.]

Exactly. And how convenient for the CIA, whose activities were being hindered by reform-minded missionaries.

Exactly. And how convenient for the CIA, whose activities were being hindered by reform-minded missionaries.

______________________________________________________________________________

July 1st, 2011, Jim Jones and the Peoples Temple Part 3, by Jim Hougan,

After entering Guyana, and making anti-communist speeches, Jones seems to have dropped off the face of the earth. Following the Guyana Graphic article of October 27, he disappears from the public record for almost six full months.

It is possible, of course, that he journeyed into the interior of that country to work among the Amerindians—but the evidence for this is so slim as to be invisible. Indeed, it consists solely of a remark by anthropologist Kathleen Adams, who wrote that Jones had at one time worked as a missionary in Guyana. Where and when is left unstated, but it was presumably during that period that Jones learned about his homicidal predecessor, the Reverend “Smith.”

The only disturbance in the empty field of Jones’s whereabouts from 10/61 until 4/62 is the information that Passport #0111788 was issued in his name at Indianapolis on January 30, 1962.

This is a considerable anomaly. As we have seen, Jones already had a passport—#22898751, issued to him in Chicago on June 28, 1960. This earlier passport, which he had planned to use on a trip to the Soviet Union, was still valid. Why, then, did someone make an application for a new passport, and who picked it up? Moreover, how is it possible that Jones’s second passport had a lower number than the one that he’d received more than a year before?

These questions cannot be answered at this time: the evidence reposes in the files of the State Department. What may be said, however, is that there is good reason to suspect that someone was impersonating Jim Jones during this period; and that, in fact, a photograph of the impostor survives. We’ll return to this subject shortly.

According to the Brazilian Federal Police, Jim Jones arrived by plane in Sao Paulo on April 11, 1962. There does not seem to be any surviving record of his point of embarkation, but it may well have been Havana. According to Bonnie (Malmin) Thielman, who met Jones at about this time, there was “a picture of him and Marceline standing on either side of Fidel Castro, whom they had met during a Cuban stopover en route to Brazil…” [Op cit., The Broken God, p. 27]

An American family, making “a Cuban stopover,” seven to eleven months after the Bay of Pigs? Physically, transportation would not have been difficult to arrange. Both Mexico City and Georgetown were transit-points for Havana. But Cuban visas were by no means issued automatically—especially to Americans making well-publicized, anti-communist speeches in Guyana. How much harder it must have been for Jones to arrange to have a photo taken of himself with Castro (who was at that time the target of CIA assassination attempts planned by yet another Indianapolis native, the CIA’s William Harvey).

It’s a peculiar, even eerie, business. I’m reminded of the man who impersonated Lee Harvey Oswald while applying for a visa at the Cuban Embassy in Mexico City during 1963. [Despite Oswald's demonstration of pro-Castro sympathies---he was arrested in New Orleans after handing out leaflets for the Fair Play for Cuba Committee (FPCC)---his impostor was not given the requested visa.]

Whatever his reason for visiting Cuba during the Winter of 1961-62, and whatever the reasons he was permitted to enter the country, Jones had no trouble entering Brazil that April. Given a visa that was valid for eleven months, he and his family traveled to Belo Horizonte where, as we have seen, Dan Mitrione had settled in as an OPS adviser at the U.S. Consulate.

Jones took rooms in the first-class Hotel Financial until he and his family were able to move to a house at 203 Rua Maraba. [Estado do Minas, "Pastor Jim Jones lived and worked in Belo Horizonte with his children," Nov. 23, 1978, p. 23.] This is a pretty street in an attractive neighborhood on a hill in one of the best parts of town. Accordingly, his new neighbors were almost all professionals: doctors, lawyers, teachers, engineers, and journalists. It was not the sort of place from which one could easily minister to the poor.

Not that it mattered. Jones’s stay in Belo Horizonte had little or nothing to do with alleviating poverty.

According to his neighbors, Jones would leave his house early each morning, as if going to work, and return very late at night. Sebastiao Carlos Rocha, an engineer who lived nearby, noted that Jones usually left home carrying a big leather briefcase; on a number of occasions, Rocha said, he saw Jones walking in Betim, a neighboring town. ["To Brazilians, Jim Jones was a CIA Agent," O Globo, Nov. 24, 1978.]

Elza Rocha, a lawyer who lived across the street and who sometimes interpreted for Jones, says that her neighbor told her that he had a job in Belo Horizonte proper, at Eureka Laundries. ["Leader of the Peoples Temple Lived in Belo Horizonte," Estado de Minas, Nov. 23, 1978, p. 1; and, from the same issue, "Pastor Jim Jones lived and worked in Belo Horizonte with his children," p. 23.]

This is a huge dry-cleaning and laundry chain, a quasi-monopoly whose central plant is serviced by more than a score of pick-up points (small storefronts) throughout the city. In essence, a customer delivers his laundry to one of the stores, where it is later collected by a delivery truck. The truck takes the dirty clothes to the central plant, where they’re cleaned, and then returns them to the store from which they came. It’s a big business.

But it’s not one in which Jim Jones ever worked. According to Sebastiao Dias de Magalhaes, who was head of Industrial Relations for Eureka during 1962, Jones’s claim to have been an employee of the laundry was false. [Ibid.] Senor de Magalhaes, and two other Eureka workers, have told the press that Jones lied in order to conceal what they believe was his work for the CIA. [Besides de Magalhaes, Elineu Pereira Guimaraes and Marcidio Inacio da Silva were interviewed. See O Globo, "To Brazilians, Jim Jones was a CIA Agent," Nov. 24, 1978.]

Still, if you didn’t know better, Jones’s cover-story served three purposes: first, it explained where he went during the day—to work. Second, it offered a theoretically visible means of support: he had a check from Eureka (everyone knows Eureka). And third, it gave Jones an alibi for a mysterious period during which he’d vanished from Belo Horizonte. According to Elza Rocha, when Jones returned, he told her that he had been sent to the United States for “special training” in connection with the machinery used by Eureka. Where Jones actually went, and why, is a unknown. [Estado do Minas, "Pastor Jim Jones lived and worked in Belo Horizonte with his children," Nov. 23, 1978, p. 23.]

Eureka wasn’t Jones’s only cover, however. He didn’t mention Eureka to Sebastiao Rocha. Instead, he claimed to be a retired captain in the U.S. Navy. He said that he had suffered a great deal in the war, and that he received a monthly pension from the armed services. The implication was that he had been wounded in the Korean conflict. According to Senor Rocha, “Jim Jones was always mysterious and would never talk about his work here in Brazil.” ["To Brazilians, Jim Jones was a CIA Agent," O Globo, Nov. 24, 1978. ]

Yet another Rocha, Marco Aurelio, was absolutely certain that Jones was a spy. At the time, Marco was dating a young girl who was living in the Jones household. [Brazilians newspapers identify the woman as "Joyce Bian." Since one of Jones's ministerial assistants, Jack Beam, is known to have joined him in Belo Horizonte in October, 1962, and to have brought his family with him, we may suppose that this was Beam's daughter.] Because of this, and because Rua Maraba is a narrow street on which parked cars are conspicuous, he noticed that a car from the American Consulate was often parked outside Jones’s house. According to Marco, the car’s driver sometimes brought bags of groceries to the Joneses—which, if true, was definitely not standard consular procedure.

Marco Rocha’s interest in Jones was more than idle, however. According to him, he was keeping a loose surveillance on the American preacher at the request of a friend—a detective in the ID-4 section of the local police department. The detective was convinced that Jones was a CIA agent, and was trying to prove it with his young friend’s help. Unfortunately, the policeman died before his investigation could be completed, and Jones left town soon afterwards. [O Globo, "To Brazilians, Jim Jones was a CIA Agent," Nov. 24, 1978.]

Gleaning the purpose behind Jones’s residency in Belo Horizonte is anything but easy. He is reported to have been fascinated by the magical rites of Macumba and Umbanda, and to have studied the practices of Brazilian faith-healers. He was extremely interested in the works of David Miranda, and is said to have conducted a study of extrasensory perception. These were subjects of interest to the CIA in connection with its MK-ULTRA program. So, also, were the “mass conversion techniques” at which Jones’s Pentecostal training had made him an expert.

Whether these investigations were idle pastimes or Jones’s actual raison d’etre in Belo Horizonte is unknown. Neither is there hard evidence that Jones’s presence was related to Dan Mitrione’s work at the Consulate—though Jones was certainly aware of Mitrione’s post. According to an autobiographical fragment that was found at Jonestown, Mitrione

Subsequently, according to that same fragment, Jones went out of his way to socialize with the Mitrione family.

“I’d heard of his nefarious activities in Belo Horizonte, and I thought ‘I’ll case this man out.’ I wasn’t really inclined to do him in, not me personally, but I certainly was inclined to inform on his activities to everybody on the Left. “But he wouldn’t see me. I saw his family and they were arrogantly anti-Brazilian…”

Because Jim Jones was a sociopath, a suspected agent of the police/intelligence community, and a man whose historical stature was intimately entwined with his false public identity as an “apostle of socialism,” there is good reason to be skeptical of the sincerity of his pronouncements about Dan Mitrione and his family. If Mitrione was, as seems likely, Jones’s first “control,” then Jones would obviously fear the revelation of that fact. In particular, he would fear the chance discovery of their past association, and the questions such a discovery would raise. To allay such suspicions, Jones may well have acted to co-opt the discovery—explaining it away in advance. Thus, he tells us that he knew Dan Mitrione as a child, and that, in Brazil, he wanted to “inform on his activities to everybody on the Left.” So it was, we’re told, that he decided to “case this man out,” and came to know his family.

This may explain the presence of a consular car outside Jones’s house: if Jones was socializing with the Mitrione family, the consular car was probably their’s. But who are the people on the Left to whom Jones refers? Whom was he going to tell about Dan Mitrione? So far as anyone knows, Jones’s acquaintances in Brazil were all conservatives. Indeed, like Bonnie Thielman’s father, the Rev. Edward Malmin, they should more accurately be described as right-wingers. And, as such, they would undoubtedly have approved of Mitrione’s work.

Nevertheless, while there is every reason to be skeptical of Jones’s memoir, it is interesting that he characterizes his relationship to the Mitriones as that of an informant, or spy. Given Jones’s sociopathic personality (not to mention his rightwing sermons in Guyana and the implications of his CIA file), it is very likely that Jones was working for Mitrione rather than against him.

While Jones is said to have gone to the U.S. Consulate often, the only person whom he is known to have seen there was Jon Lodeesen. [ Besides Marco Rocha's remarks about a car from the American Consulate, Bonnie Thielman recalls that Jones often went to the Consulate on unknown business.]

On October 18, 1962, Vice Consul Lodeesen wrote a peculiar letter to Jones on Foreign Service stationary. The letter reads:

On October 18, 1962, Vice Consul Lodeesen wrote a peculiar letter to Jones on Foreign Service stationary. The letter reads:

Signed by Lodeesen, there is a redundant post-script to the letter, requesting that Jones “Please see me.”

While the letter itself is entirely opaque, an attachment to it is not. This a passport-type photograph of a man who, despite his mustache and receding hairline, looks remarkably like Jim Jones—or, more accurately perhaps, like Jim Jones in disguise. While one cannot be certain, it may well be that the photo is related to the peculiar circumstances under which a second passport was issued to Jones—while the first passport was still valid. [The letter from Lodeesen, with the photograph attached, was provided by the FBI to attorneys in the Layton case.]

While the letter itself is entirely opaque, an attachment to it is not. This a passport-type photograph of a man who, despite his mustache and receding hairline, looks remarkably like Jim Jones—or, more accurately perhaps, like Jim Jones in disguise. While one cannot be certain, it may well be that the photo is related to the peculiar circumstances under which a second passport was issued to Jones—while the first passport was still valid. [The letter from Lodeesen, with the photograph attached, was provided by the FBI to attorneys in the Layton case.]

That it was Jon Lodeesen who contacted Jones is significant in its own right. This is so because Lodeesen has been a spy for much of his life. According to Soviet intelligence officers, he is a CIA agent who taught at the US intelligence school in Garmisch Partenkirchen, West Germany—a sort of West Point for spooks. Subsequently, he worked at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow—until he was declared persona non grata for suspected espionage activities. Kicked out of the Soviet Union, he went to work for Radio Liberty, a CIA-created and -financed propaganda network based in Munich. There, he was Deputy Director of the Soviet Analysis and Broadcasting Section. [SeeCIA in the Dock, edited by V. Chernyavsky, Progress Publishers, Moscow (1983): "Saboteurs on the Air: A Close-up View" by Vaim Kassis and Leonid Kolosov, pp. 147-67.] More recently, Lodeesen was recommended for work with a CIA cover in Hawaii. [The letter (dated January 12, 1983) was from Ned Avary to Ron Rewald, then CEO of the Hawaiian investment firm Bishop, Baldwin, Rewald and Dillingham.] In a letter to the proprietor of the cover, Lodeesen was described as “fluent in the principal Russian tongues” and an expert on “Soviet double agents, dissidents and escapees.”

Just the man, in other words, to handle the passport problems of an American psychopath who’d applied for a visa to visit the Soviet Union; who’d made repeated trips to Castro’s Cuba; who had two valid passports at the same time; and who seems to have been the victim of, or a party to, an impersonation.

II.8 JONES IN RIO

Friends of the Jones family in Belo Horizonte are agreed that he lived in the city for a period of eight months, beginning in the Spring of 1962. He then moved to Rio de Janeiro.

Once again, Jones seems to have been following Dan Mitrione’s lead. In mid-December, as the Jones family packed for the move to Rio, Mitrione left Belo Horizonte for a two-month “vacation” in the U.S. At the beginning of March, he returned to Brazil—but not to Belo Horizonte. Instead, he found an apartment in the posh Botafogo section of Rio de Janeiro.

There, he was not far from Jim Jones, who was recumbent in equally elegant surroundings, having found an expensive flat in the Flamengo neighborhood. [Jones's address in Rio was #154 Rua Senador Vigueiro.]

According to Brazilian immigration authorities, who are said to keep meticulous records, the Jones family left Rio for an unknown country at the end of March. And they did not return.

According to Jones, however, he and his family lived in Rio until December of 1963. The assassination of President John F. Kennedy (in November of that year) was the stimulus for their return to Indiana.

There is, in other words, a nine-month period in which Jones’s whereabouts are at least somewhat questionable. One would think, of course, that there would be a great many records and witnesses to the matter. Unfortunately, that isn’t the case. Those members of Jones’s family, and his associates, who might have seen him in Rio either died at Jonestown—or were too young at the time to be certain where they were in 1963. [For example, Jones's natural son, Stephan.]

The issue should have been settled, of course, by the newspaper articles that appeared in Brazil after the Jonestown massacre. These were stories with local angles, describing Jones’s life in Brazil. Curiously, however, none of the articles originating in Rio quote identifiable sources. This is quite unlike counterpart articles written about Jones’s stay in Belo Horizonte. In the latter, almost everyone seems delighted to get his name in the paper. In Rio, nobody wants to be identified.

By far the most extensive account of Jones’s stay in Rio de Janeiro was published in a newspaper that is thought by many to have been owned, or secretly supported, by the CIA. This was the English-language Brazil Herald. [Brazil Herald, "The little-known story: Jim Jones' early days in Rio de Janeiro," by Harold Emert, December 24-26, 1978, p. 9.]

According to the article, it was “through a friend in Belo Horizonte” that Jones “found a job as a salesman of investments” in Rio. The source for this information is unstated, as is the identity of Jones’s friend in Belo Horizonte.

The company for which Jones is said to have worked was Invesco, S.A., which had offices in the Edificio Central in downtown Rio. [There have been persistent rumors that Jones, while in Rio, was employed by a "CIA-owned advertising agency." Invesco, while not an advertising agency, is the only firm to which these rumors could possibly refer. It is certainly the case that any number of Brazilians suspected that its American owners were working for the CIA.] At least, it did until the firm went bankrupt, under scandalous circumstances, in 1967. Though this occurred more than ten years before, Invesco’s former assistant manager—Jim Jones’s boss—was still in Rio at the time of the Jonestown massacre. An American who’d come to Brazil in the late 1940s, and stayed, he was willing to confirm Jones’s employment at Invesco—but not much more. And he did not want his name used.

“As a salesman with us,” he told the Herald, “(Jones) didn’t make it. He was too shy and I don’t remember him selling anything,”

Applied to Jim Jones, this is a remarkable statement. Is it possible that someone who sold monkeys door-to-door in Indianapolis during the Fifties could be too timid to sell mutual funds in Rio de Janeiro during the bull-markets of the Sixties? The mind boggles. Here is a man who is said to have talked 900 people into killing themselves for what he hoped would be his greater glory…and he was “too shy”?!

“We hired him on a strictly commission basis and as far as I know he didn’t sell anything in the three months that he worked for us,” the former assistant manager said.

This, too, is an interesting remark because it implies that, while Jones worked for Invesco, there would be no record of the fact as a consequence of his failure to record any sales. Without putting too much of a point on it, the reader should know that commission-only sales’ jobs are favorite covers for CIA agents in foreign countries. This is so because the agent is not required to produce any cover-related work-product for his civilian boss (i.e., he doesn’t need to sell anything at all)—because he’s working strictly “on commission.” At the same time, salesmen working on commission are expected to travel, and to cultivate a broad spectrum of acquaintances.

Thus, whether Jones was working for Invesco or not, it served as a good cover for whatever else he might have been doing.

Still, if the sales-job which Jones is supposed to have held down produced no income at all, how did he support himself? According to the Brazil Herald, he “was receiving donations of checks sent by his followers in the US. His ex-boss notes having seen Jones’ briefcase filled with checks.” This is possible, of course, but extremely unlikely. Membership in the Peoples Temple had plummeted during Jones’s absence, dwindling from 2000 members in 1961 to fewer than 100 parishioners at the time of the Kennedy assassination. By the end of 1963, the electric and telephone bills had gone unpaid, and disconnection threatened. The idea that parishioners were supporting Jones in high style, by sending him personal checks, is ludicrous. Not only did they not have the money, but Jones would probably have starved had he depended upon cashing small personal checks, written on Indianapolis bank accounts, in Rio de Janeiro.