February 1958, American Heritage Magazine, Vol. 9, No. 2,

Unwanted Treasures of the Patent Office; Thousands of products of Yankee genius, in miniature models, have survived a British invasion, three jires, and a sale at Gimbels, by Donald W. Hogan,

Archived,

While the British were busily engaged in putting the torch to Washington on the evening of August 24, 1814, Dr. William Thornton, superintendent of the Patent Office, stood aghast by a window in Georgetown watching the Capitol, of which he was the chief designer, go up in flames. But the next morning, when he learned that the Patent Office too was threatened with fire, he mounted a horse and dashed back into the city, one of the first Americans to return.

Quickly he approached a Colonel Jones, who had been assigned to burn that part of the city, and begged that Blodgett’s Hotel, which a few years before had become the Patent Office and museum for its models, be spared from the flames. According to his own report, he stood amid the smoldering ruins of the city and successfully overwhelmed the Britisher by charging that the destruction of “the building … which contained … hundreds of models of the arts … would be as barbarous as formerly to burn the Alexandrian Library for which the Turks have since been condemned by all enlightened nations.” Blodgett’s Hotel was the only government building spared in the razing of Washington.

This seems to have been the high point of the federal government’s concern for its collection of patent models, which since that time has been decimated by three other fires, two federal economy waves, three auctions, a bankruptcy, and a sale at Gimbels.

Seven weeks before the last of the thirteen original states ratified the Constitution, Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, Secretary of War Henry Knox, and Attorney General Edmund Randolph became the Patent Commission. When they opened for business on April 10, 1790, they immediately established the requirement that a working model of each invention, clone in miniature, be submitted as part of the application.

This requirement was kept in force until 1870, when a change in the law was made necessary by quarters so bulging with models that there was no room for examiners, and the submission of a model was made discretionary with the commissioner of patents. By 1880 the requirement was dropped altogether with the wry exception of flying machines—for which the requirement was also dropped after 1903 and Kitty Hawk. (But the Patent Office still demands physical proof of the pudding before it will issue a patent lor a perpetual motion machine.)

From the very start the models—the idea for which sounds like a Jeffersonian notion—became a tail that wagged the dog. Their number and bulk dictated the division’s move in 1810 from an office in the Department of State to Blodgett’s Hotel. Congress had appropriated $10,000 to purchase the hotel and $3,000 to renovate it, insisting that the two larger of four rooms assigned to the Patent Office be devoted to displaying the models. The rest of the building, except for two smaller rooms, was given over to the General Post Office.

Congress would brook no untidiness in the exhibition. A committee reported within three months of the appropriation that “although many models have already been deposited in their new quarters, the manner in which they are placed tends to confusion and to sink the establishment into contempt. It is hoped that habit will not operate to make this perpetual.”

The chiding was effective, and Blodgett’s Hotel, which had originally housed the United States Theater, the first in Washington, regained and even surpassed its earlier fame as a point of interest for travelers to the capital. Foreign visitors were shown the models as a proud demonstration of American inventiveness, and on Sundays it became a local custom to stroll through the rooms and see what was new.

But, even though the models were the focal point of interest in the Patent Office, no record of their kind or number appears to have been made until January 21, 1823, when, for no apparent reason, a clerk at least attempted a listing.

His catalogue showed a nation still more concerned with agriculture and building pursuits than with industrial development. It listed 95 nail cutters, 66 pumps, and 65 plows as against 45 looms, 28 spinning machines, and 3 boring machines. Of “propelling boats” there were 38; of carding machines, 8; of threshing machines, 20; and of winnowing machines, 25. There were 13 bridges, 26 sawmills, 17 water mills, 7 windmills, 14 steam mills, 26 water wheels, 56 presses, 3 stocking looms, 10 fire engines, 1 machine for making barrels. 6 flax-dressing machines, 6 file-cutting machines, 16 cloth-shearing machines, 10 straw cutters, 12 locks, and 2 guns. The specific listings came to 635 and evidently so exhausted the cataloguer that he lumped the remaining 1,184 models as for “various other purposes” and gave a total of 1,819 models in all.

This was the only listing of the models ever made—with the exception of one which was paid for in 1908 but which, when it was sorely needed in 1925, could not be found.

After 1823 the number of patent models at Blodgett’s Hotel increased until by 1836 there were about 7,000 of them, lodged against more than 10,000 patents issued. A committee of Congress reporting on the need for a new building declared that “a great number of them, supposed to be 500, from want of room, have been stowed away in a dark garret.” (It was an ominous precedent.) In July, 1836, a law was passed allowing for construction of the new building. Ground had hardly been broken, six months later, when at three o’clock on the morning of December 15 fire was discovered in the Post Office section of Blodgett’s Hotel. Within a matter of hours the building was burned to the ground, and with it went every record and every model owned by the Patent Office.

Describing the calamity, a Senate investigating committee spoke ruefully of “a pride which must now stand rebuked by the improvidence which exposed so many memorials and evidences of the superiority of American genius to the destruction which has overtaken them.” And Congress, perhaps impressed by this rhetoric, promptly appropriated $100,000 for restoration of “3,000 of the most important [models] … which will form a very interesting and valuable collection.”

At first Patent Commissioner Henry L. Ellsworth worked diligently both at having the burned models restored or rebuilt and at outfitting the showrooms of the new Patent Office. Shortly, however, he complained to the secretary of state, under whose department his office came, that many inventors had failed to co-operate and that it was impossible to remake the models without their help. This was particularly true of such inventions as the plow with cannon for handles to fight oft sudden Indian attack—of which the burnt model was the only one ever made.

But if Ellsworth was thwarted by the apathy of inventors when it came to restoring models, he was overcome by their enthusiasm for submitting new ones. The new Patent Office building at Seventh to Ninth between F and G was only partially completed by 1844, but already the Commissioner was forced to complain that unless the job were hurried the collection of models would force the working stalf out onto the street. “The increase of models renders daily the transaction of business more difficult,” Ellsworth wrote in his annual report. (In fact, he was so discouraged by the influx of new models that he managed to spend only $25,588.91 of the $100,000 appropriated for restoration of the old ones.)

By 1856, however, three wings of the new building were completed. Its great halls, the east and west wings, were fitted out as showrooms, and the building again became a tourist attraction, a display of national ingenuity.

Then came the Civil War. Invention was fantastically stimulated. Models, which had been coming in by the hundreds every year, now arrived by the thousands. Several of them came each day to each of the twenty examiners and were thrown on shelves until papers were completed and issued. Then, just as quickly, the models were tagged with basic information and carted to the galleries, unclassified, where higgledy-piggledy they were tossed’ into a case or onto another shelf. An army shoe would land next to a drill; a corset beside a sword.

By 1876, William H. Doolittle, acting commissioner of patents, reported that the building was so clogged with models that the public had been barred from seeing them for lack of room.

He estimated that 175,000 models had been crowded into the galleries and that they were increasing by 10,000 to 14,000 a year. “Immediate relief,” he said, “is necessary.” Even though a law of 1870 had made the submission of models discretionary, it appeared the Commissioner had not wanted to take upon himself the responsibility for rejecting them. But neither could he function in their midst.

Temporary relief came on September 24, 1877, when fire again broke out in the Patent Office. Although the blaze was confined to the west and north wings, and neither of them was destroyed, 160 cases of models, estimated to contain 76,000 in all, were ruined.

Some of these were replaced through a $45,000 appropriation, and still new ones poured in. Finally the law had to be changed again, this time to prohibit the sending of a model unless demanded by the Patent Commissioner.

But still no record was made of how many models had been restored or even how many were in the Patent Office, and estimates varied by as many as 25,000, depending on whether the guesser was a patent examiner tripping over them while trying to do a day’s work or a congressman looking to save the price of renting some place to put them. It is known, however, that 246,094 patents had been issued by 1880 and that perhaps 200,000 of them were represented by models. Added to these were thousands of models which had accompanied applications that were never completed.

By 1893 the Patent Office estimate appears to have won out, for that year Congress allowed the renting of the Union Building at G Street between Sixth and Seventh streets, N.W. No attempt was made to arrange the models for display in the Union Building. They were simply stored in fantastic disarray throughout the building, even though Congress was under the impression it was paying for an exhibition hall.

This folly was not discovered until 1907, when the owners of the Union Building attempted to raise the rent and thus precipitated a congressional investigation. The annual number of visitors, it came out, was none. In retaliation, without thought as to why there were no visitors, Congress in 1908 decided to sell all the models, first giving the Smithsonian Institution six months to pick out those it wanted. The Smithsonian managed to find only 1,061 worth keeping. At a public auction, 3,000 models of inventions that had failed to receive patents were sold for $62.18.

During the next two decades those remaining unsold, amounting to 155,939, were carted about repeatedly—back to the Patent Office, to a leaky basement under the House of Representatives, to the basement of the District of Columbia’s Male Work House, and at last to an abandoned livery stable. Finally, in a congressional economy wave in 1925, it was found that more than $200,000 had been spent for storage and moving since 1884; rather than squander any more money on museums, Congress again elected to sell. An act was passed on February 13, 1925, appropriating $10,000 for the sale and creating a three-member commission to again select important models for the Smithsonian and other recognized museums.

By late November, the Smithsonian had selected about 2,500, and 2,600 more were taken either by other museums or by inventors. Another 50,000, which had been unpacked, so crammed the floor space that an immediate auction was ordered, and on December 3, 1925, they went for $1,550. Thomas E. Robertson, patent commissioner, reported to Congress that “this was thought to be a good figure.”

The buyer of the 50,000 models was never officially identified; the General Supply Committee kept scanty records. Circumstances, however, point to Sir Henry Wellcome, who in 1926 came back to acquire the remaining 125,000, cases and all, unopened, without even the formality of a public auction. He paid $6,540.

Sir Henry began life in Wisconsin in frontier days—his earliest memories were of holding the basin while his doctor-uncle dressed the wounds of pioneers who had been battling Indians—but he had become a British subject during World War I. He founded Burroughs, Wellcome & Co., a large and successful drug house, and was knighted by George V for his services to medicine and pharmaceutics. Given to offbeat causes (he once endowed a trust to provide translations of textbooks for Chinese medical students), Sir Henry decided to start a patent-model museum and to store his new acquisitions at the Burroughs, Wellcome plant in Tuckahoe, New York, until he could get around to building it.

When Sir Henry died ten years later, at the age of 82, the models were still there, packed in their original cases, unopened. The trustees of his estate, after lengthy consideration of what to do with them, finally decided to sell. It took them two years, but they got their price—$50,000.

Their customer was Crosby Gaige, Broadway producer and gourmet, whose collections to date had been limited to books on eating and cooking and to laboratory equipment for making his own tooth paste.

Gaige brought the models to Rockefeller Center with the kind of fanfare usually reserved for the circus. Without delay he cracked open the first few cases. Then, on August 8, 1938, he managed to entice several representatives of the press into being present while an expert locksmith twirled the dial of a model crystallized-iron safe.

The tumblers clicked; the door swung open. Inside was a paper. The writing was faint, but the signature was legible—A. Lincoln. The paper was a petition for a patent on a flatboat with air chambers for floating it over shoals, invented by Lincoln in 1849. Flash bulbs popped and the models were page one news.

Within a few more days, Gaige plucked from the cases the original model of the Gatling gun, the first dentist’s chair, and the first egg beater (Timothy Earle, 1866). He also had a long list of bedazzled customers, and by early October, 1938, he and his silent partner, Douglas G. Hertz (fight manager, movie actor, mule trader, survivor of the Lusitania, and former owner of the New York Yankees football team), had retired with a neat profit from speculation in Americana by selling out to a group of businessmen for $75,000. The Lincoln paper, its purpose served, disappeared as mysteriously as it had arrived.

The new owners also had money-making ideas but lacked Gaige’s theatrical imagination. They incorporated under the name of American Patent Models and unpacked 25,000 models, a tiny part of the collection, amid mutterings to the press that it was an outrage the government had ever sold them. The vast remainder, about 2,600 full cases, was shipped to the Neptune Storage Warehouse in New Rochelle, New York. Some 500 of the unpacked models were then fitted into special crates and sent out in three separate caravans across the country, to be displayed in department stores and other showrooms for a fee. The rest were kept at Rockefeller Center.

Between 1939 and 1941 the models, uncatalogued, unclassified, and on public display, proved to be no more of an attraction than they had been years before. Neptune Storage filed a lien of $7,954 for warehousing the unopened crates. Rockefeller Center wanted its rent. American Patent Models, in a desperate effort to raise money, reduced prices on all models to $1 each and for quick cash sold a collection of Civil War ordnance to an unnamed buyer. An unlisted number of other models went in the same manner. Then came bankruptcy. In 1942 a court ordered the company dissolved and the models auctioned for whatever they would fetch over and above Neptune’s bill (which had grown to $10,814) and another $800 to warehouses in Minneapolis, Salt Lake City, and Oakland, California, where the traveling exhibits were stranded.

At this point O. Runclle Gilbert, an auctioneer, learned of the models. Gilbert brought in several partners and shortly, in exchange for $2,100 plus the storage charges, they were the owners of about 200,000 patent models. Seventy-five huge trailer truckloads later, the models were in Gilbert’s barns at Garrison, New York, but their adventures were far from finished. Gilbert’s partners, eager for profit, insisted on a new auction, and when more than 3,000 persons came to see a display of 2,000 models which opened at the Architectural League in New York City on April 14, 1943, they were confident of success. But despite great spectator interest only three actual bidders showed up on the day of the sale. Among them they bought 400 models. Back to Garrison went the remaining 1,600; the round trip, display, and other costs had exceeded the gross by $3,000.

Gilbert then began systematic unpacking. Soon, with the help of his wife and three hired hands, Gilbert was delving into boxes which presumably had not been opened since 1908 and which the Smithsonian Commission of 1925 had not had a chance to examine.

Slowly, as the models were unpacked, identified, and classified—for the Gilberts believed they would sell best in groups describing the complete development of a particular item—they were moved into a stucco house on the estate, where they filled fourteen rooms. The rest of the house was rented to a young couple and their children.

Identification was easy in the case of models which bore labels; some of them were stamped with dates prior to 1836 and evidently were among those reconstructed after the fire of that year. But many of the models were without any identification at all and these were set aside for further research.

One group of models, including farm equipment and an early baseball mask, was sold to the Farmer’s Museum and the Baseball Museum at Cooperstown, New York. By Spring, 1945, several other groups, including one which traced the entire history of the sewing machine, were also ready for sale. There were perhaps 20,000 models in the stucco house at Garrison—close to 3,000 of them various forms of bolts and nuts—when fire broke out. The young couple and their children were saved, but nothing else.

Stunned, the Gilberts decided to leave the remaining 2,000 unopened cases in the barns until they felt better. Then, some four years later, the idea of a museum of their own began to intrigue them. As a start they purchased a vast barn in Center Sandwich, New Hampshire, and moved in about 1,000 models chosen at random. They started charging 25 cents, 50 cents, then $1, and found that, no matter what the price, Center Sandwich was good for 75 visitors a day. They also found that sometimes people who stopped could help them decide what some of the objects were. One man told them they had the model of the first rotary press; another found the first Mergenthaler typesetting machine, which he promptly took apart but never returned to put back together again.

Others guessed that some of the models, with their fine tooling and hand workmanship, must have cost more than $1,000 to make. When word of this reached Gilbert’s partners in 1950, the pressure was on again for another sale.

This time the idea was to invade Gimbels, a proposition which the department store welcomed with open arms. “Gimbels is nuts over patent models. You’ll be nuts over them too,” cried their advertisements.

Hastily, without time for classification, the Gilberts ripped open 200 or 300 more cases in the Garrison barns and shipped the contents to Gimbels in New York and Philadelphia. Among them were the “Bretzel bending machine” invented by a Mr. Bretzel, who formed his crackers in the shape of a B (the public quickly decided a pretzel was easier to pronounce), and such novelties as a hen house which, when the chicken went out for scratching, dropped down a sign saying, “I am out. You may have my egg.” There were also an 1825 plug of navy chewing tobacco and an 1869 parlor bathtub. In one lot was some powdered milk patented in 1863; Mr. Gilbert added water, tasted it, and pronounced it “sweet as ever.” The prices ran from $1 to $1,000, the latter tag attached to the Gatling gun.

Again there were thousands of spectators but few buyers, with the exception of Gilbert, who took advantage of his partners’ disappointment to buy them out at cost. He shipped the 5,000 or so models which had been stranded at the two Gimbels stores (about 600 had been sold) to his museum at Center Sandwich, where they remained until 1952, when he purchased as a new museum an abandoned hospital at Plymouth, New Hampshire, and moved the entire display there. But in his barns at Garrison, still unopened, unseen since 1908, there are cases which contain anywhere from 100,000 to 120,000 more models.

Gilbert calculates that with the new museum he has put well over $85,000 into the models since acquiring them fifteen years ago, and he does not intend to invest any more. Those that are still packed will stay that way until he sees a good reason to open them. Sometimes he wishes the government would buy the collection back and put it someplace—Ellis Island, for instance. In the meantime he operates the Plymouth museum every summer. And when he and Mrs. Gilbert are at their home in Garrison, they occasionally go over to the barns and look at those rows on rows of boxes.

Donald W. Hogan is assistant city editor of the New York Herald Tribune. A free-lance writer whose major interest is American history, he has contributed articles to several national magazines.

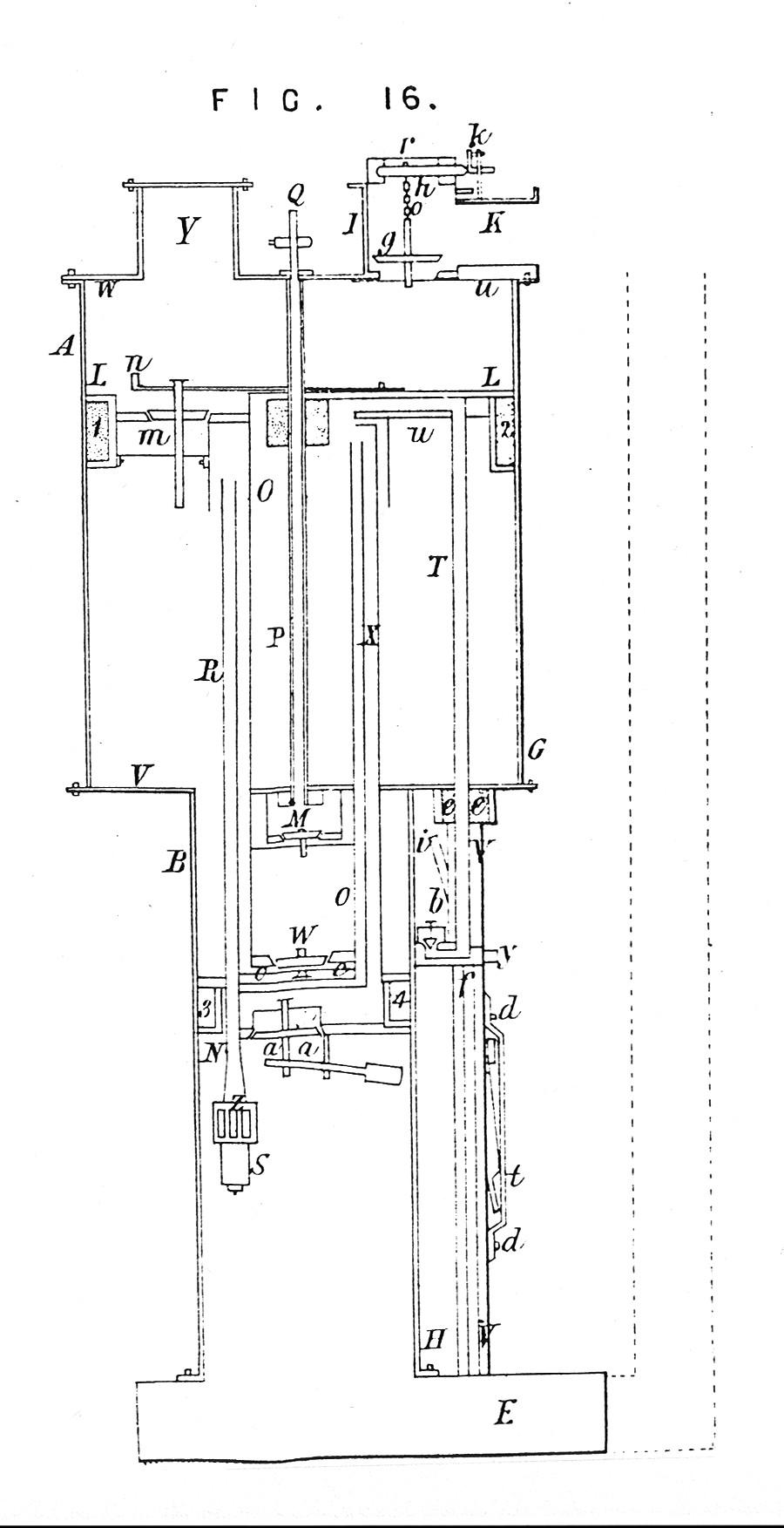

Possibly the engine for the Columbian Maid. Rather than having a working beam operating all the pumps of a steam engine, Rumsey made them nest within each other, as hollow pistons. Very compact and light, but difficult to build and still not thermally efficient

Possibly the engine for the Columbian Maid. Rather than having a working beam operating all the pumps of a steam engine, Rumsey made them nest within each other, as hollow pistons. Very compact and light, but difficult to build and still not thermally efficient